The Being is the Doing:

The Foundational Place of Therapeutic Presence in AEDP

By Benjamin Lipton, LCSW

Senior Faculty, AEDP Institute

156 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1116

New York, NY 10010

benliptonnyc@gmail.com

Abstract. The primary didactic objective that bridges all my teaching is to convey that in AEDP, the “doing” of therapy is, first and foremost, the therapist’s way of being as a therapist, and that this being transcends the concept of therapeutic stance. Everything we “do” in AEDP begins with the therapist’s ability to be present in body and mind, while being oriented to what is happening in the client, and staying open to being explicitly impacted by what is happening in the intersubjective space of the moment between therapist and client. This is what Diana Fosha has named “feeling and dealing while relating,” what is now known more broadly recognized in the work of Shari Geller as Therapeutic Presence (TP). In this article I propose my model of therapeutic presence, Active Empathy: Presence, Attunement, Intention, Resonance, and Reflection (PAIRR), built upon my synthesis of embodied presence phenomena, and emphasizing the active, relational thrust of the processes. Active Empathy is engaged when we surrender to the improvisational emergent truth of the moment while trusting that our left-brain knowing will come to our aid when necessary. A session transcript demonstrates the application of Active Empathy and highlights the act of being in embodied therapeutic presence.

Throughout my first decade as an AEDP therapist, I had been trying to identify and name exactly what it was that I found to be most transformational for my patients from the toolbox of experientially oriented skills and intervention strategies that I was learning and assembling. While a therapeutic stance of affirmation and delight along with the specific skills of privileging transformance, moment-to-moment tracking, making the implicit explicit, and of course, metatherapeutic processing, are all necessary and powerful tools for processing emotions to completion and potentiating lasting psychological change, somehow none of them entirely captured what seemed to be the foundational therapeutic driver of transformation for my clients.

I have always felt in my gut that whatever this driver was, it clearly had to be informed by the radically relational approach of AEDP. Yet the psychotherapy language intended to capture the importance of the therapeutic relationship did not adequately capture what, for me, was most powerful about it. “Common factors,” “Unconditional positive regard,” “therapeutic alliance,” “intersubjectivity,” “secure attachment” “corrective emotional experience,” etc. each describe essential aspects of an effective therapeutic relationship, but they all felt too intellectualized—too experience distant—to resonate deeply within me and speak for my truth. I am so grateful to the wisdom of the AEDP community of therapist learners for helping me to find the answer to my longstanding question: What is at the core of co-creating change for the better in AEDP?

For nearly two decades now, when participants in presentations reflect on a clinical video that I have just shared, two categories of observation almost always emerge. The first category includes comments about economy of language and energetic entrainment. Here are some examples:

“I’m getting that it’s really not so much about the words, as it’s about how you are….”

“AEDP looks kind of deceptively simple, doesn’t it? It can seem like not that much is happening really. But I’m getting it—it’s about tracking the process around the words more than just the content. There’s so much happening beneath your words and in between them.”

“You are saying so much without saying very much at all. Wow!”

The second category of reflections by participants in my AEDP trainings focuses on the powerful sense of safety that so often resonates with viewers of AEDP video

“It’s like you’re saying, “I’m here in State 2 and it’s ok and you can join me here when you’re ready…”

“You made the client feel so safe. You’re like the embodiment of a secure attachment figure.”

“Once they realized you were safe and they really felt safe, not just by saying so, but in their actual experience, at least for that moment, then the healing just flowed…”

Each time I hear comments like those described above, I sense that I’ve succeeded in a primary didactic objective that bridges all my teaching: conveying that in AEDP, the “doing” of therapy is, first and foremost, the therapist’s way of being as a therapist, and that this being transcends the concept of therapeutic stance. Reflections and observations from my AEDP colleagues eventually enabled me to recognize that the powerful fuel for my own particular AEDP change-engine is the depth of my embodied presence. When I generate and connect to deep, embodied presence, treatment with my clients progresses—even if that progress may look difficult or challenging. When less presence is online, things do not go as well. Beyond therapeutic intention or specific stance, how we are being in ourselves and with our clients is the foundational clinical intervention of our attachment-based, neurobiologically informed, transformationally driven model.

Everything we “do” in AEDP begins with the therapist’s ability to be present in body and mind, while being oriented to what is happening in the client, while staying open to being explicitly impacted by the intersubjective results. This is what Diana Fosha has named, “Feeling and dealing while relating” (Fosha, 2000, 2003). It corresponds to what is now known more broadly in the field of psychotherapy as Therapeutic Presence (TP) (Geller, 2011, 2017). Learning and teaching about TP in AEDP has become a passion of mine. Thanks to the important work of Geller and her colleagues, and our own AEDP Institute research initiative, conversations about TP are broadening from the realms of theory and clinical practice to include emerging empirical research on its trans-theoretical nature and therapeutic effectiveness (Geller & Greenberg, 2002, 2010, 2012; Geller, 2011, 2017).

Geller asserts that TP is “a trans-theoretical approach to creating safety” that precedes and accompanies any model-specific techniques (2017). She describes TP as multi-faceted: a method of therapist preparation, a subjective experience, and a relational process in therapy. Rooted in a phenomenological approach, AEDP complements this conceptualization with the assertion that TP is not only a precondition for transformative therapy and a method for attuning in the therapeutic process, but also a powerful affective change process in itself (Lipton & Fosha, 2011) that can be made explicit and metatherapeutically processed in the service of deepening and broadening relational and intrapsychic capacities in both client and therapist.

Thus far in this history of AEDP, the focus on the moment-to-moment tracking of a patient’s emergent experience has resulted in the complementary, moment-to-moment experience of the therapist taking a relative back seat on the therapeutic journey that leads to healing. While referenced in a few articles and the subject of at least one dissertation (Prenn, 2011; Schoettle, 2017; Tavormina, 2017), the exploration of therapist experience in AEDP is generally underrepresented in the AEDP literature. It may be that in the interest of leading from the get-go with radical empathy–a foundational tenet of AEDP–another foundational tenet, making the implicit explicit, in this case related to one’s own experience as a therapist, has been underprivileged when it comes to an AEDP therapist using their own experience to guide the therapeutic work beyond moments of empathic self-disclosure with patients (Fosha & Prenn, 2017). It is positioning TP in the foreground of what we work with as AEDP therapists, rather than to the background that we work from, to which I am deeply committed and explore further in this article.

In AEDP, Therapeutic Presence (TP) describes processes that are both vertical, within the therapist’s own body and mind, and horizontal, conveyed through a therapist’s energetic disposition, therapeutic stance, and relational availability to being somato-sensorally impacted— in heart and mmind—by a client. Feeling and dealing while relating—the AEDP therapist’s relational North Star—references the foundational role of attachment theory in AEDP. Some key attachment-based AEDP components that inform this concept are: promoting an embodied sense of safety; privileging affirmation and intersubjective delight; leading with authenticity; moment-to-moment tracking of the therapeutic process (both verbal and nonverbal, in patient and in therapist); a focus on affect regulation; “going beyond mirroring” and actively helping (Fosha, 2000, 2010, Frederick, 2010); selfdisclosure in the service of undoing aloneness and decreasing shame; and receptivity to being impacted by our clients. Together, these ideas inform a therapeutic stance that is welcoming, grounded, embodied, affirming, encouraging, delighting, explicitly emotionally engaged, and regulating.

Therapeutic Presence is the embodied, clinical manifestation of the knowledge that right-brain-toright- brain, affect-regulating processes are crucial for brain growth and creating secure attachment. It is this empirical truth that speaks to the essential place of TP in AEDP. Unless our “left-brain,” intellectual knowledge and theoretical understanding gives way, in the moment, to privileging right-brain, intuitive experience and attunement, our knowledge is of little therapeutic value—and potentially counter-productive. The tension between knowing and not knowing, tracking self and other, but not coercing or predicting, is essential to the success of therapy.

Active Empathy: The PAIRR Model

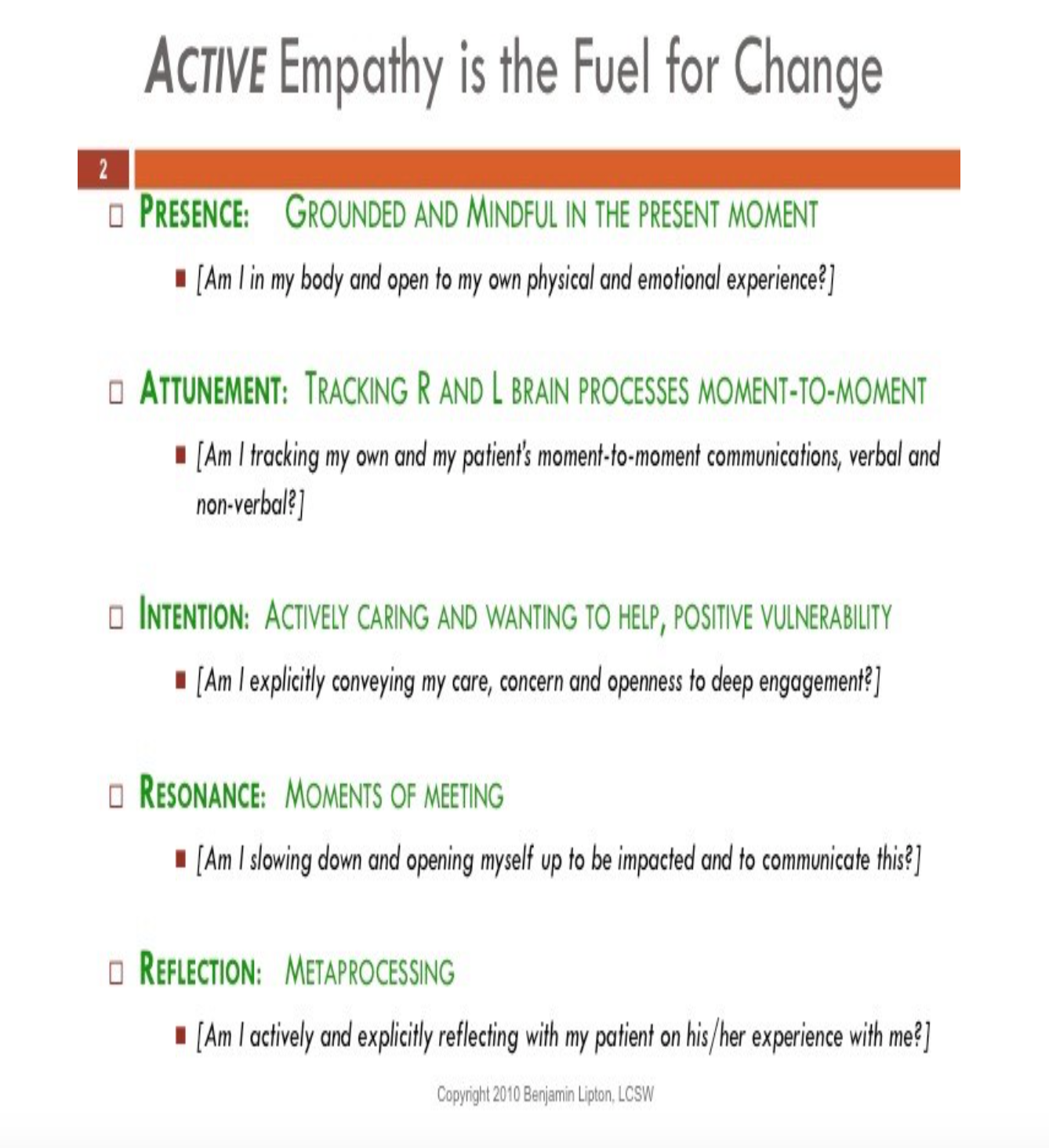

Several years ago, as I was trying to put together the pieces of the puzzle that I thought informed what was foundational to healing in AEDP, I developed a synergistic concept that I called Active Empathy© and which I labeled the “fuel for change” in AEDP (Lipton, 2014). Reviewing the literature on relational processes in therapy, the neurobiology of attachment, somatosensory processes, and mindfulness, I synthesized five key concepts that together comprised this concept of Active Empathy: Presence, Attunement, Intention, Resonance, and Reflection (PAIRR©, see Diagram in Appendix).

Accompanying each of these component parts of Active Empathy© is a key question for therapists to ask themselves as they are working to be deeply present with clients. My desire in labeling this synthesis of key concepts as Active Empathy© was to emphasize the active, relational thrust of these processes and the stance of deep engagement that informs them and is central to AEDP, rather than the more widely held stance of measured engagement or neutrality that informs many therapy models.

Several years later, when I discovered the important work of Shari Geller, I had an unexpected True Other experience. As I read Geller’s (2017) book on TP, I was delighted to learn that her empirically validated model incorporates most of the same concepts as PAIRR. In fact, in a recent copresentation with me through the AEDP Institute (Geller & Lipton, 2018), Geller suggested that PAIRR© more accurately reflects aspects of her model of TP than the specific phenomenon of empathy which is incorporated into title of Active Empathy (For a discussion of the distinction she makes between her definition of TP and empathy, see Geller (2017, p. 26) ). What follows is a brief description of the five component concepts that together inform PAIRR©.

Presence. We need to be attuned to ourselves in order to attune to others (Geller, 2011, 2017). Presence (as distinct from TP which is a more comprehensive concept) describes our capacity to be grounded and mindful in the present moment. Interoception, the ability to sense what is happening inside of us, in our bodies, is a fundamental skill for cultivating and deepening our awareness of the present moment (Craig, 2002). The therapeutic question that orients us to presence is, “Am I aware of what is happening in my body and open to my own physical and emotional experience?”

Attunement. Presence within ourselves allows us to attune to others. Attunement describes a subjective sense of authentic connection, of sensing someone deeply. It refers to how we focus on the other and take their experience into our own inner world and then allow it to shape who we are at that moment (Siegel, 2003). To accurately attune to another, we must be open to the bottom-up flow of intersubjective phenomena rather than any top-down expectations or requirements of how the other could or should be feeling or acting at any given moment. Theory of mind as manifest in reflective self function is paramount (Fonagy et al., 2002). We must have a willingness to not know and a readiness to say, “Tell me more.” Moment-to-moment tracking of both right and left brain processes in the client and therapist is fundamental to attunement. The therapeutic question that orients us to attunement is, “Am I tracking my own and my patient’s moment-to-moment communications, verbal and non-verbal?”

Intention. Intention refers to the directionality of many of the qualities that make up the therapeutic stance in AEDP. As AEDP therapists, our intention is to lead with authenticity, delight, affirmation, and privileging of our client’s transformance strivings. We hold a healing orientation (rather than a pathologizing one) of actively caring and wanting to help in addition to a willingness to be open and to be impacted by our clients. The therapeutic question that grounds us in our intention is, “Am I explicitly conveying my care, concern and openness to deep engagement?” Resonance. Resonance refers to the physiological and emotional markers of coordination such as heart rate, breath patterns, physical behaviors and gestures, posture, gaze alignment, and emotional synchrony. These are the constituents of moments of meeting, of becoming a “We” (Geller, 2017; Schore, 203, 2012; Siegel, 2010). As we orient ourselves to resonate with our clients, once again we are not focused on knowing as in predicting, but rather on being open to, accepting and syncing up with whatever is coming our way from our client verbally and nonverbally. The therapeutic question that facilitates resonance is, “Am I slowing down and allowing myself to be impacted by my client and to explicitly communicate this when helpful?”

Reflection. Refection refers to AEDP’s unique contribution to the understanding of how new experience is encoded and integrated into explicit memory by reflecting on it. Metatherapeutic processing, reflecting explicitly on the experience of change in therapy as it is unfolding moment-tomoment, is the vehicle for engaging in reflection and cognitive integration of sensory experience with our clients. Additionally, by metaprocessing a client’s embodied experience of presence, attunement, intention and resonance, we make the impact of these implicit experiences explicit and relationally experiential, as well. This opens the door to additional positive change processes as alternating rounds of experiencing and then reflecting on that experience potentiate a spiral of transformations (Fosha, 2000). Moreover, in this way, left brain learning joins right brain experience in the service of creating explicit memories of whatever is transpiring in the therapy process both intrapsychically and relationally. The therapeutic question that facilitates metaprocessing is, “Am I actively and explicitly reflecting with my client on their experience with—and of—me?” The fortuitous and unexpected acronym, PAIRR©, that revealed itself as I was creating the list of contributing concepts to Active Empathy© conveys the embeddedness of this concept in a relational context. Moreover, the consecutive Rs in the acronym reference the iterative nature of the AEDP concept of metatherapeutic processing. In my own practice, PAIRR© has become a foundational tool for helping me to cultivate and carry through the qualities necessary for making good use of all my other AEDP clinical techniques.

What follows is a transcribed vignette from a therapy session with a client of mine that I hope will tangibly bring to life what I have been describing thus far and illustrate the transformational power of therapeutic presence as both a foundation for and a focus of AEDP treatment.

Transcript: The Birth of Self

This vignette is from a course of therapy with a client of mine, whom I will call “Sara”1 who had endured an early history of significant neglect. One of many children from a poor family who immigrated to the United States shortly before her birth, she grew up in a confusing and dangerous world where demands for basic family survival—putting food on the table and a roof over everyone’s heads—overrode all other individual needs and consumed the daily attention of her parents and older siblings. From shortly after birth, she was left in the care of her 9-year-old sister while her parents and teenage siblings worked night and day to support her and her five siblings. Not surprisingly, when her parents finally returned home late in the evenings, there was little energy left over for engagement and nurturance with their children. Moreover, Sara’s twin sister had feeding challenges as an infant. In fact, it was this sister’s medical challenge that provided the impetus to come to the US. In the context of this high-risk situation, whatever little energy Sara’s parents had for nurturance focused solely on feeding and caring for Sara’s sister and Sara inadvertently would often go hungry as a result.

To add further challenge, the cultural values of Sara’s family subjugated girls and women to the authority of men. The expectation was that Sara would be meek and obedient and inhibit any personal ambition for the sake of caring for the needs of her father and male siblings. Despite these inimical circumstances, Sara’s inherent resilience and capacities emerged in powerfully adaptive and impactful ways. Against her family’s wishes, she moved across the country, put herself through college, and eventually went to graduate school to become a teacher. Along the way, she discovered Buddhism, became very engaged with meditation, and ultimately became a leader in her spiritual community. However, she found it very challenging to engage in intimate relationships. Eventually, it was because of this that she sought therapy.

The following transcript is from a session several weeks into treatment when Sara was reflecting on the depth of relational deprivation in her childhood. As the transcript begins, we are collaboratively working to recall an important experience from the last session when she became conscious of my loving disposition toward her.

C: Yeah…so then I was saying something about (shy smile, hands lift)…I don’t know what I need, that’s one of my issues…

Th: Uh-huh…yeah.. [I’m feeling a sense of poignancy and curiosity, too]

C: Is…it’s hard for me to know what it is I want…or require…

Th: Mmmm,hmm,…[I’m feeling a sense of congruence with C.]

C: I can’t remember where I went then (smiles shyly again)…um…

Th: I can’t at this moment, either…I have to acknowledge…(C nods, swallows)

C: I think it was something about…the level of attentiveness…the quality of…your being with me last week that moved me and I think…brought me back to the power of the gaze…your gaze…and…

Th: And the absence of it in your family, as one of five children, in the middle…[I’m feeling the resonant excitement of getting coordinated.]

C: Right…

Th: And a twin…and being out on the patio…[C was left out on the patio in stroller for hours as an infant while mother dealt with her twin sister and older siblings]

C: In the backyard…yeah…

Th: Just alone in your stroller…[Attuning to the felt sense of aloneness]

C: Mmm-hmm..

Th: That was a heart rending…image for me…[We are co-constructing the felt sense of a memory, and I am sensing into her bleakness, the aloneness, and the pain as well as the client’s efforts to stay at a distance from it.]

C: And I think also the fact that it was a male showing concern, you know…(head slightly tilts, brows furrow)…it’s a man’s face…looking…tenderly and with attention…[referring to my visible attunement and empathy for her during our last session]

Th: Mmm…

C: Yeah, I’m sure that my father…(gazes towards floor) I was gonna say not that my father didn’t [look at her that way] and yet I don’t recall (chuckles)…

Th: I saw that in your face…yeah…[attuning to her pain]

C: That kind of look….

Th: And that touches you…[resonating]

C: (nodding slightly, steady gaze with Th)

Th: What’s coming up?

C: (head tilts, gazes away)…Mmmm…well with my dad…(removes scarf from neck, begins to speak, pauses)…you know, I think my dad…must’ve been very terrified or traumatized himself from his own…childhood…his own father was abusive…lost their home…grim poverty…so the stories were like going to school with no shoes or…

Th: Wow…[I’m shaken by sudden emergence into reality of what has become a social meme of exaggeration about the poverty of previous generations in the US—“When I was a kid, I walked 10 miles to school, with no shoes, in the snow, with dogs chasing me, etc….]

C: And the Christian Brothers barking (imitates the teachers). Come up here! (sternly)…a lot of humiliation…and…shame and…he left school at 12…going work in a factory…I think he was probably the first wage earner in the family, so he was probably supporting the family at that point…12 years old….I think…because his self wasn’t recognized so he couldn’t recognize (hands lift slightly, palms face up)…us…[I’m deeply touched and pained by this evocative portrait of her father’s childhood and the implicit impact on C.] The classic scene is dad…holding forth at the table and we’re sitting around and my mother is serving us and…I’m listening, spellbound cause he’s an eloquent speaker or so I think (hands lift higher)…But really he was a rigid, dogmatic, unyielding, narrow man (hands lift, palms face each other).. .

Th: Wow…..[resonating with the cruelty and neglect C endured]

C: Yeah….yeah…so…but you know I used to think he was God…and he held the truth…um…(glances at lap)…so I wasn’t also the kind of daughter he wanted…as it turned out, being gay, he could never accept it…So, I mean all to say that…I don’t have (one hand lifts, swirls at wrist, slight smile, head turns, brows raise, index finger and thumb press together, gazes down)…I don’t have the experience of a (voice trembles, sadness rises)…tender…accepting, loving gaze…from a man…

Th: Mm-hmmm…until now…[I make the implicit explicit and directly acknowledge my loving gaze toward C.]

C: (smiles, sniffs, swallows, maintains gaze with me smiling tenderly)…So I’m drinking it in…in drafts…

Th: Yeah, I see that…(C reaches for tissues)…I see that and I feel it. [I disclose my being deeply impacted by her experience of my loving gaze.] And I have to tell you that the words you use to describe your experience, the tender, accepting, loving gaze…they feel exactly congruent with how I feel…those feel like just the right words…[affirmation and disclosure of resonance]

C: (takes deep breath, head rests against back of chair, maintains gaze, challenging window of affect tolerance) …Ok…(sniffs)…

Th: You’re holding your breath…[said playfully, as if to a toddler. I’m resonating with a sense of youngness and that we are entering the territory of a young girl’s experience and co-creating a new working model of intersubjective delight and connection.]

C: (chuckles with delight—she is being seen—and a little anxiety)…head leans forward, staring intently)

Th: Mmm..what’s that saying do you think…with that kind of held breath…[I am curious, and a bit playful.]

C: (brows lift, head slightly tilts, breathing resumes)…..It’s like I’m a little girl and I’m being held…and patted on the back (one hand lifts and makes slight swirling gesture)…

Th: Hmmm…

C: A feeling of…safety and strength…(head lowers, gaze maintained)…and it being ok…

Th: Mmm-hmmm….[resonating with her emerging safety]

C: Of being held in the okayness….(exhales)…

Th: Yeah…[paraverbal affirmation and attuning to her settling]

C: (chuckles several times, blows nose, deeper breathing/absorbing the experience of my presence and deep, embodied engagement)…

Th: (C laughs then Th laughs)….I find myself wanting to say, that I have such an urge to say, so I’m gonna go with it because…it’s so…insistent…I just want to say, “Hi Sara! (C laughs with delight, wipes tears from her eyes with tissue)…Hi…really…Hi…(C sniffs, continues to maintain gaze and breathing is deeper) What’s happening?

C: It’s…I mean it feels very early…it feels very early, very preverbal…(reflecting on experience)

Th: Yeah…[resonating, attuning, encouraging—all with one word]

C: Um…and so there’s just a calming inside and…a sweetness and a kind of sense of the body being just whole…and can..can kind of just bathe in the being held…and um…(smiles)…and feel good to be here…and that there’s so much to know and discover…(said with delight and wonder as if she were empathizing with the experience of her own younger self discovering this new way of being with another)

Th: Uh,Huh…

C: And find out through…(one hand lifts and makes rolling gesture)…just the answer is I guess the word resonance is a good word…being resonated to…(deeper breathing) and it’s like you know…I don’t have to do anything. It’s sort of like it seems whatever I do is…in itself of interest to you…

Th: That’s true…[big smile of delight and resonant wonder]

C: (smiles, nods) Yeah…yeah…

Th: I don’t think I would have had those words…because I’m also in a sort of right brain experience with you, but as you say what you said, it feels exactly right…I feel SO engaged…interested…[authentic self-disclosure]

C: Yeah…(spontaneous accessing of her somatic experience) you know, I’m just noticing the parts of me…there’s something across my shoulders or my neck…

Th: Mm-hmm..

C: Oh…kind of a passing noticing maybe a passing holding there…

Th: Hmmm…

C: And yeah, the head feels heavy…

Th: Mm-hmm..

C: And then down into my stomach, genitals…my arms, left arm…right arm…legs, feet…and just the whole…mmm…the whole torso (cadence of speech is flowing, relaxed, soft)….how it feels…um…as just perfectly relaxed and just that sense of being able to just be…and a teariness about that…cause it’s like something can let go…and it’s um…it’s like I’m being held so I don’t have to hold myself (brows furrow)…and I’m just seeing what that difference is…some kind of releasing of…

Th: Yeah…notice that…[gentle, encouraging affirmation and reassurance]

C: (gaze is steady, head makes slight, relaxed rolling movements)…it’s a releasing of some kind of tension of having to hold myself up…and to do…and that you know, in this way, there’s really nothing I have to do….the being is enough….the being is plenty to be going on with…(deeper breaths, maintaining gaze, swallows)…And there’s something that says…there’s even something in my mind that’s saying…”How come I can’t do this on my own?” You know, which of course, meditation is and yet…(hands lift and swirl)…something’s happening here that…is a complete letting go…I’m wondering how I don’t have the emotional release with the meditation…(one hand lifts and swirls)…I think what it is is that in meditation the body drops off, the mind drops off…

Th: Mm-hmm…[I notice some anxiety rise in me as C is moving into more cognitive place of sense-making, potentially as a way of defending against the emergent affect within her. I’m also aware that she is trying to make sense of this new experience of deep relational presence and my holding her emergent Self that I believe was the “missing” ingredient in her meditation experiences.]

C: And for me…it’s not that it’s disembodied…but it’s that…there’s you know, the no-self…

Th: Yeah….it’s sort of like the…[I sense I’ve interrupted C.] I’m sorry…I didn’t want to interrupt you…go ahead…[My anxiety leads to misattunement and a disruption.]

C: Yeah [unconscious confirmation of the disruption], no…go ahead…I think it’s the no-self which of course you know is the…is the Buddhist truth and I get that…(index and finger and thumb press together in spontaneous mudra)

Th: Of course you do…[affirmation, attempt at repair]

C: It’s easy of course, coming from where I’m coming from…but this is the…this is of course, the embodied…self…it’s…I mean you could say it’s also the no-self…

Th: You could, but that doesn’t feel experientially accurate to me…maybe it does to you…[I’m resonating with her anxiety about allowing herself to fully surrender to her somatosensory experience of being emotionally held by another.]

C: Well you say it’s Sara….it is (repeats spontaneous mudra)…

Th: Right that’s what I was just connecting to…that what I felt in myself…needing to say was…”Hi…Sara!” [emphasizing the word Sara to reference the specific, embodied Self of the client]

C: Right (emotion rising, deep breaths)….

Th: And that…touches something very deep in you…[resonance, attunement and affirmation to make her implicit rise in affect explicit and support her processing of it]

C: Yeah…(begins to cry)

Th: Stay with this…it’s ok…I’m right here…[affirmation, “We-ness,” explicit support]

C: (audible, slow sobs)

Th: Yeah…yeah…[paraverbal affirmation and holding]

C: I don’t know…what that is…

Th: Uh-huh…you don’t know what what is?

C: (both her hands lift and swirl)…I don’t know what the emotion is but it’s..I guess it’s a way of…something is found (deep breath….pained facial expression)…

Th: Mm-hmm…(C maintains gaze)

C: And that, I guess, wants to be here…wants to be found…(head softly undulates side to side, deep exhales through mouth)…I know what it is…

Th: Yeah.. what did you notice…what was the experience in your body?

C: It’s….the whole body is seized with…there’s a (hands lift and sweep upward, palms face in)…feeling in my legs…seized with something….up to my neck, to my head…there’s a heaviness (head leans against chair)…

Th: Yeah…[resonating with the depth of affect that is rising up in her]

C: Something that says, “I’m here.” (voice trembles)

Th: You’re here…(C audibly sobs)…and I see you….yes, you are here…(C sobs). [I feel within me a powerful and deep desire to actively affirm and witness the emergence of C’s Self].

C: Then it’s…but who am I? [cognitive defense]

Th: You are this….[C’s question creates anxiety in me as I fear her defending against more deeply processing her emotional experience. I blurt out this statement in what feels like a desperate effort to bypass her defense but in doing so I create a rupture as indicated by her next statement when she says that the affect suddenly comes to a full stop.]

C: Then it stops…

Th: Yeah, I think what I just said wasn’t so helpful…[self-disclosure, effort at attunement and repair of rupture]

C: No, all you said is, “You are this.”

Th: I know but somehow…

C: But what is this?

Th: Exactly….[I affirm her in effort to soften defense, regulate anxiety and get us back on track with emotion processing.]

C: There’s heaviness in my legs again..a weightedness (exhales, pauses, sniffs, head rests against chair)…of wanting to sit up straight….

Th: [I’m sensing a deepening of the disruption. So I make an attempt to organize our cocreated experience and explicitly self-disclose in the service of inviting a more complete repair.] I think that was just such a big moment…that we just had together…and that you had in yourself…and I think I got like….a little dysregulated….(C chuckles with confirmation)…so I said something…

C: Oh no (smiles, her words confirm the disruption caused by my mistake)

Th: …just to say something (C chuckles) …cause it felt so big and so important….huge…

C: Well it’s….it’s here again…there’s…. there’s something weighted…[The reconnection to her emergent affect confirms that the repair is complete and we are back in sync. The less I have said to now in our process, the more effective was the work. This is because the focus here needs to be on the explicit being of the therapist as a loving other who actively accompanies and witnesses and holds, not on the doing of making statements or figuring things out with words. In fact, that sort of doing generally creates a disruption].

Th: Uh-huh…[encouragement, affirmation, holding]

C: There’s something that says “I’m here”…and so it does feel like something is born…whatever that means…and it’s fully born…

Th: Wow…[I am genuinely in awe of what is happening here.]

C: That’s fully…inhabiting this…

Th: Mmmm….

C: I think it’s saying alright…I can be here…

Th: Mmmm…[I nod and smile.]

C: As in….I guess as in, “It’s safe to be here…” (exhales, maintains gaze)…Then the question is, “Am I using meditation to leave?”

Th: Before you go there…

C: Yeah..

Th: Could you just give yourself a moment to be here? [attempt to bypass the defense]

C: Thank you…[explicit gratitude confirms attunement of my intervention.]

Th: Just to kind of sense out that experience of, “It’s safe to be here…”

C: Yeah…I’m checking it out…

Th: Good…take all the time you need…

C: (slight nod and lift of brows, deep breath, swallows, exhales through mouth several times, audible sobbing becomes guttural moans.) [As I resonate with this experience, I associate to the client as a baby left alone and hungry in her carriage on the back patio. I resonate with the felt sense of this.]

Th: Ohhh kayyy…[leans forward]….mmmm..ohhh kayyy…[I extend paraverbal reassurance and move in to offer regulation and comforting.]

C: (exhales, groans continue)

Th: Can you see me here? [checking for degree of dissociative process]

C: (gazes at Th, nods through groaning)

Th: I’m right here…I am right here…(C opens eyes while groaning). [My face conveys availability, tenderness, and empathic resonance with her pain.]…I am right here…

C: Mmmmm…(C settles, groaning ceases, body is still, she maintains gaze and takes deep, regulated breaths)…

Th: Such big feelings…yeah…[I say this with amazement as one would with an infant in an effort to convey positive wonder and help organize their experience.]

C: (smiles, head juts forward slightly, deep exhale, rests head against chair)

Th: What’s happening now?

C: I’m taking you in…it’s like…who’s this? What’s this…[C says this with same sense of childlike wonder as I was conveying a moment ago. This is about emergent curiosity, not defensive intellectualizing. Th smiling, continues to stay leaning forward.] (C’s resting face is still. Then C smiles slightly.)

Th: What’s it like to take me in? To check me out…[metaprocessing this new experience]

C: Yeah I think I’m ready to suckle [We both laugh heartily.]

Th: Mmmm….[resonant delight and affirmation]

C: (with happy vitality) I think I’m ready to be held right up close…in your arms and just…and then just get lost in your eyes or just…completely merge…into that ocean…the ocean of your chest (hands lift, palms face in, smiling)…and your eyes and just um…(hands make undulating gestures)…and like merge…feel that oneness…in that kind of sea of oneness and kind of a bliss…

Th: Mmm…[Affirming the articulation of this corrective emotional experience]

C: I mean, as it is, there’s the sense of separateness, of course, right here…but I could just see (smiles, hands lifted, eyes glance around)…that’s the original state you see if things go well…there’s the…there’s the embodied oneness you see…the oneness but in the body cause I’m being completely held in my body…[We continue to silently gaze with mutual, embodied presence for nearly a minute.]

Th: So, I’m aware that we’re near the end today…

C: Yeah, so now I’m back to my…adult (smiles)…self and I…I don’t know…how this experience…(readjusts body to sit more upright)…affects me. I mean I don’t know how it….(halting expression indicates emergent, realization affects of recognition are forming).

Th: What do you notice just right now? [staying moment-to-moment with metaprocessing]

C: Um…I feel clear…and…present…[core state]

Th: Mm-hmmm…

C: And…and separate but connected…[core state]

Th: Mm-hmm…

C: And…hmmm….I wonder how the rest of the day will unfold…(spoken with a lilt of curiosity, chuckles)…and…um…and curious about what it’s like to be you…you know…working with me (smiles).

Th: Sure…that’s a question? Or a statement? [simultaneously wanting to welcome the question and not interfere with her emergent reflections.]

C: Yeah, it’s a statement, yeah…

Th: Ok…you’re welcome to ask those questions too, just to be explicit about that…

C: And I can imagine…

Th: Mmm….what do you imagine? [metaprocessing and solidifying access to a new working model of intersubjective delight]

C: Well I can imagine it’s very….it’s alive…and I can imagine it’ll be a little…”What’s happening now…where is this?…’Cause you can’t learn this by the book…and you do very, very well…just…(smiling)…being…this trusting…that whatever happens is ok self…[resonant delight and appreciation]

Th: (nodding) Hmmmmm….

C: Which gives infinite permission (warm smile, open gaze)…

Th: I’m glad…[join her gaze for several seconds]. And I’m aware that you shared this, as you said, from sort of being back in your adult self…

C: Mmm-hmmm..

Th: I’m just wondering how’s the little bitty baby self doing…who I felt lucky enough to…to have some sort of…(C’s head turns slightly, eyes narrow)…the words you use was a birth process in some way…

C: Yeah, I think the little baby self established that it’s…that…the human realm is…negotiable…(humorous smile)

Th: Huh…[resonating with, emphasizing this emergent, curious new potential way of being in the world]

C: It can…it will survive…[There is a profound depth of presence in C as she states this.]

Th: Yeah…[I am deeply, deeply moved.]

C: Yeah negotiable is a strange word for a baby to use…

Th: It’s like it doesn’t…what comes to mind is…. it doesn’t have to be alone..

Th: Ah…yes…I am so happy to know this [self-disclosure of my experience].

C: I think…I really felt this (hands lift, palms face up to gesture being held)…this being held…

Th: I felt it too…

C: It, the younger me, felt yes, being…tended to, being cared for…being accompanied…being…(head tilts)…attuned to…being met…

Th: Mmmm….in both senses of that word I think…(C smiles, nods)…joining…just meeting..

C: Yeah…

Th: This delightful….feelingful…

C: Yeah….(nodding, playfully smiling, delighted by my delight)

Th: Wide-eyed…little baby girl…[mirroring wide-eyed curiosity followed by a big, warm smile] So nice…[Affirmation]

C: (smiles, palms press together in Namaste gesture, head bows)…

Th: So can I ask you one other quick question before we leave…what would you like to take with you from our experience together today, if anything? [A transformational process has unfolded. I want to leverage every possibility to metaprocess the experience and deepen access to the new way of being that is developing.]

C: (smiles) Well you have a way of looking and you raise your eyebrows…it’s kind of like when a baby burps or something, you kind of go. “Oh!” (delight and surprise, laughs)…it’s like, “Oh!”…(again models the playful curiosity and loving delight)

Th: Uh-huh (smiling)

C: Which is so tender and loving and again, everything is worthy of…delight…

Th: So…would you like to take that image of me with you?

C: (eyes close, nods affirmatively)

Th: I’d like that too…very much

As AEDP therapists—and human beings, for that matter—we need to open our hearts and minds and allow our true selves to reach out and touch the souls of our clients who are bravely coming forward to share of themselves in ways that past injuries have taught them not to do. This, I believe, is the foundation of deep relational healing. If we are asking our clients to access presence and to commit to authenticity and being real, then we must demonstrate a willingness to lead the way ourselves. We do this by cultivating Therapeutic Presence. And in this endeavor, our bodies are our tools.

To my mind, Therapeutic Presence brings to the fore the fact that therapy is, among other things, a form of art. Like all artists, the AEDP therapist must be deeply immersed in the theory and technique of a robust model: the phenomenology of the 4 states, the therapeutic stance of affirmation and delight, techniques for softening defenses, regulating anxiety, deepening affect, undoing aloneness, and metaprocessing, etc. But this immersion in knowledge must eventually open up to the paradoxical wisdom that we must also let go of anticipatory knowing. We must recognize the ways in which a reliance on prediction will disrupt the fundamental, deeper, (both literally and metaphorically) sense of being, in heart and mind, that we are aiming for, and to trust that what needs to happen can and will happen if we hold to the core AEDP principle of feeling and dealing while relating (Fosha, 2000). Geller (2017) writes:

My use of the word sensing rather than knowing or thinking was purposeful—in this state of flow, overthinking actually interferes with the implicit knowing that rises inside. This reflects the paradigm shift from thinking (knowing through cognition and analysis) to knowing from the inside out of embodiment (knowing through sensing and being in relational connection).

Attachment research with parents and children—just regular parents and children, not therapists with post-graduate degrees— demonstrates that healthy relationships emerge from implicit contexts of presence and relational capacity (Cassidy, 1994; Hughes, 2007; Main, 2011; Tronick, 2007). If no overt clinical knowledge is needed to create the context for people to flourish, then in some ways, the deepest message may be that we have to unlearn the intergenerational, unconscious as well as conscious transmission of “doing” in clinical psychology, so that we can really be with the being: heart to heart, body to body, mind to mind.

At the same time, we cannot force presence. We cannot will it to happen. Again, we must work with the parts of us that are ambitious and are needing to do something so that we can let them go and simply be—be available, be authentic, be kind, be helpful, be mindful, be embodied, be aware of self and other. Knowledge and technique are essential. However, we must be steeped in them only to be able to trust they will come to our aid when necessary. Then we must surrender to the improvisational, emergent truth of the moment. If we are grounded in our ourselves, regulated, openhearted, appropriately boundaried but not constrained, then we are optimally positioned to be the relational conduit to psychological healing that our clients are asking us and need us to be.

Footnote

1: Sara is not the client’s real name.

References

Cassidy, J. (1994). Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2-3), 228-249.

Craig, A. D. (2002). “How do you feel?” Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 3 (8): 655–666.

Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E., & Target, M. (2002) Affect regulation, mentalization and the development of the self. Other Press.

Fosha, D. (2002). The activation of affective change processes in AEDP. In J. J. Magnavita (Ed.). Comprehensive handbook of psychotherapy. Vol. 1: Psychodynamic and object relations psychotherapies New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Fosha, D. (2003). Dyadic regulation and experiential work with emotion and relatedness in trauma and disordered attachment. In M. F. Solomon & D. J. Siegel (Eds.). Healing trauma: Attachment, mind, body, and brain. New York: Norton.

Fosha, D. (2007). Transformance, recognition of self by self, and effective action. In K. J. Schneider, (Ed.), Existential-integrative psychotherapy: Guideposts to the core of practice New York: Routledge.

Fosha, D. (2007, Summer). “Good spiraling:” The phenomenology of healing and the engendering of secure attachment in AEDP. Connections & Reflections.

Fosha D. (2009). Emotion and recognition at work: Energy, vitality, pleasure, truth, desire & the emergent phenomenology of transformational experience. In D. Fosha, D. J. Siegel & M. F. Solomon (Eds.), The healing power of emotion: Affective neuroscience, development, clinical practice (pp. 172-203). New York: Norton.

Geller, S. (2017). A practical guide to cultivating therapeutic presence. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Geller, S. & Greenberg, L. (2002) Therapeutic presence: Therapists’ experience of presence in the psychotherapy encounter. In Person-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapies, 1(1- 2):71-86.

Geller, S., & Greenberg, L. (2010). Therapist and client perceptions of therapeutic presence: The development of a measure. Psychotherapy Research 20(5): 599-610.

Geller, S., & Greenberg, L. (2012). Therapeutic presence: A mindful approach to effective therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hughes D. (2007). Attachment-focused family therapy. New York: Norton.

Lipton, B., & Fosha, D. (2011). Attachment as a transformative process in AEDP: Operationalizing the intersection of attachment theory and affective neuroscience. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 21 (3), 253-279.

Main, M., Hesse, E., & Hesse, S. (2011). Attachment theory and research: Overview, with suggested applications to child custody. Family Court Review, 49, 426-463.

Russell, E., & Fosha, D. (2008). Transformational affects and core state in AEDP: The emergence and consolidation of joy, hope, gratitude and confidence in the (solid goodness of the) self. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 18 (2), 167-190.

Schore, A. (2003) Affect regulation and repair of the self. New York: Norton.

Schore, A. (2012) The science of the art of psychotherapy. New York: Norton.

Siegel, D. (2003). An interpersonal neurobiology of psychotherapy: The developing mind and resolution of trauma. In M. Solomon, M. & D. Siegel (Eds.), Healing trauma: attachment, mind, body and brain. New York: Norton.

Siegel, D. (2010). The mindful therapist. New York: Norton.

Tronick, E. (2007). The neurobehavioral and social-emotional development of infants and children. New York

Appendix